Green’s Point Accessible Exploration

Explore the Seafloor

Come for a dive at Green's Point! Let images and videos introduce you to some of the amazing species that live in the rockweed forests. Once you're back on the surface, learn about the point's historic lighthouse.-

Green's Point From the Air

Green's Point marks the entrance to Letete Passage: a thoroughfare used by vessels to enter Passamaquoddy Bay en route to wharves at St. Andrews, St. Stephen, and St. George. Letete is derived from the French "la tete," which means "the head," and likely refers to the headlands that bracket the passage. Video Description: We see Green's Point from the air, filmed by a drone. A white and red lighthouse sits on the end of a narrow peninsula. It is mid-tide, and as we fly over it, we see the rocky shores surrounding the point. We fly back over the lighthouse heading out to sea. We glimpse a navigational marker that marks the currently submerged Morgan's Ledge. The camera pans over the calm, sun-dappled sea, before we glimpse the western isles on the horizon. This video has no sound.

-

Green's Point Lighthouse

A steam-powered fog alarm was placed on Green's Point in 1879, with the lighthouse being added in 1903. The lighthouse was manned until 1996 when it was fully automated. In 1999 it was decommissioned (apart from the fog alarm), and it is now managed by the Green's Point Light Association as a museum and recreational facility.

(Photo: Jolinne Surette)

-

Rocky Shore

The tidal range at Green's Point is over eight metres. At low tide, in the mid-shore (littoral) zone, the abundant seaweed drapes over the rocks. But on the low shore, the rock is often bare of seaweed. This is caused by high levels of sea urchin grazing. We call this an urchin barren.

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/HMSC)

-

Shore Survey

Biology students from Mount Allison University conduct a transect to study how species diversity changes down the shore. The students visited Green's Point as part of a field course held at Huntsman Marine Science Centre.View species

(Photo: Adrian Kiva)

-

Common Eiders

Large flocks of common eiders (sea ducks) gather to feed together. Birds in front of the flock dive first in search of food, while the individuals in the back follow. The flock then moves offshore, where they rest and digest their food. Non-breeding females, called aunts, help look after young eiders and protect them from predators.View species

(Photo: Nick Hawkins)

-

Bald Eagle

Bald eagles are very common in eastern Canada. They often nest in forested areas near the water. They have a very varied diet including fish such as salmon and herring, smaller birds, reptiles, crabs, and rabbits. They can use their strong talons to catch prey, but are also happy to scavenge. Bald eagles often take advantage of carcasses they find on the seashore or inland.View species

(Photo: Steve Cooke)

-

Stone Tool

This projectile point (spear, dart, or arrow head) was found on the shore at Kelly's Cove on the west side of the isthmus connecting Green's Point to the mainland. Several artifacts dating from about 4000 years ago to the time of European contact have been found in this area. Ancestral Peskotomuhkatiyik (Passamaquoddy First Nation) made these tools.

(Photo: Austin Paul)

-

White-Tailed Deer

Seaweed is relatively high in energy and protein . Deer sometimes feed on it, particularly in areas where terrestrial food is sparse such as on islands. White-tailed deer are strong swimmers and may travel between coastal areas by sea. The lighthouse keeper on Machias Seal Island in the Gulf of Maine was surprised to spot one there in 2014. Biologists think it swam to the island from the nearest mainland – 16 kilometres away.View species

(Photo: Steve Cooke)

-

Green Crab

Green crabs are an invasive species. They are common on the shore and in the shallow subtidal zone around Green's Point. They are native to Europe and were first recorded in Canada in 1951. They are such an efficient predator that they can out-compete native crab species for food. They also disrupt eelgrass beds, which are an important habitat for juvenile fish, and destroy shellfish beds.View species

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/HMSC)

-

Horse Mussels

Horse mussels are common around Green's Point both on the shore and in the sublittoral zone. Here they occur in small clumps between rocks. In other areas of the Bay of Fundy they are found in much higher densities, forming extensive biogenic reefs (reefs made from layers of hard-bodied animals). Northern sea stars feed on the horse mussels.View species

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/HMSC)

-

Sand Dollars

On the sandy seabed around the point, sand dollars are abundant. These are relatives of sea stars. Scientists think the low profile of sand dollars is an adaptation to reduce drag from water currents. This allows them to live in high current areas on unstable substrate. Sand dollars feed on small particles in the sediment and can reach densities of hundreds per square metre . Scientists think that they are the second most important factor, after major storms, in reworking surface sediments.View species

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/HMSC)

-

Barnacles and Periwinkles

When the tide comes in it covers rocks on the shore. Barnacles close when the tide is out but now open to feed. They are related to crabs and lobsters and use their legs to kick food into their mouths. Periwinkles roam over the rock, scraping off algae and juvenile animals with their radula. This is a rigid, ribbon-like structure with many tiny teeth that the periwinkle uses to tear up food and bring it into its mouth.

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/HMSC)

-

Diver Rockweed

A Huntsman diver explores the rockweed forest around Green's Point. The fronds of rockweed can reach up to two metres in length. When the tide is in, air bladders along the length of the frond hold it up in the water. This allows the plant to get the maximum exposure to light to photosynthesize.View species

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/HMSC)

-

Tidepooling

When the tide is out, you can find large tidepools on the shore around Green's Point. At low tide these provide a refuge for sea creatures. Underwater, much of the rock is pink. Stone-like coralline seaweed covers it in a thick crust. Search behind boulders and under ledges and you might find crabs, sea stars, and urchins. If you would like to have a go at tidepooling, check out our education resources.

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/Huntsman Marine Science Centre)

-

Green Urchins

Green sea urchins are very abundant around Green's Point. They are most common in depths of under 10 metres where they can reach densities of over 28 mature urchins per square metre. There is a commercial fishery for urchins in this area. Fishers SCUBA dive to collect urchins or use drags from the boat. Fisheries and Oceans Canada regulate the fishery using a quota system. They are mainly exported to countries such as Japan where their gonads (reproductive organs) are considered a delicacy.View species

(Photo: Claire Goodwin/HMSC)

-

Northern Rock Barnacle

Barnacles are suspension feeders. Here we see them beating their cirri (modified legs) to filter zooplankton from the water. In short, a barnacle can be imagined as a shrimp stuck by its head to a rock and kicking food into its mouth. This species can beat its legs around 60 times per minute. The number of beats varies depending on water temperature, food availability, and current. Video Description: In extreme close up we see a group of yellow-white barnacles on a rock. They are submerged. Their leg-like cirri frantically beat. We can hear the breathing of the diver filming them.View species

-

Jonah Crab

Video Description: We watch as a buried Jonah crab emerges from the muddy seabed. Its mouthparts flicker as it edges its legs out. Then, trailing plumes of silt, it is off, running sideways over the uneven seabed. It passes many green urchins and scrambles over clumps of horse mussels. The plentiful horse mussels at Green's Point provide lots of food for Jonah crabs.View species

-

Bristled Longbeak Shrimp

Video Description: In close-up, we watch a bristled longbeak shrimp as it rests on a pebble and sand seabed. Stepping its delicate legs, it comes toward us sideways. Its antennae almost touch the camera. We can hear the exhalations of the cameraman.View species

-

Atlantic Deep-Sea Scallop

Northern sea stars can eat scallops. This scallop doesn't seem bothered though – maybe the sea star is too small to be a threat. Scallops can sense the chemicals given off by predators. When one gets too close, they clap their shell valves together and swim away. Video Description: We see an Atlantic deep-sea scallop resting on the seabed. Along the edge of its shell its white tentacles and many eyes are visible. A northern sea star crawls over its shell. Next to the scallop are a pair of green sea urchins.View species

-

Seals

The rocks of Splitting Knife Ledge and Black Ledge are favourite haul-out sites for both harbour and grey seals. It can be tricky to tell the two species apart. When viewed in profile, grey seals have a long, straight, “Roman,” nose. In contrast, the harbour seal has a shorter, curved nose and a distinct forehead, giving it an appearance like a spaniel. Grey seals are also bigger than harbour seals – the grey is up to 2.5 metres long, and harbour seals only up to 1.7 metres.

(Photo: Nick Hawkins)

-

Great White Shark Attack

During the summer of 2019, there were several sightings of a great white shark feeding on seals at Black Ledge. People thought the shark might be taking advantage of moments the seals were distracted by whale watching vessels to strike. We know sharks feed on seals and are often observed near seal colonies in other parts of the world. Yet, it was unusual to see this behaviour in the Bay of Fundy. Video Description: We travel past rocks exposed by the tide, aboard the Jolly Breeze whale watching vessel. We can see seals hauled out on the rocks and the head of another seal that is swimming beside them. There is a splash of white water. Onlookers gasp and exclaim as the water turns red, and we see large fins flailing. “It's a shark!” a man exclaims. “Oh no!” cries another. The shark has caught a seal. The splashing subsides. A red tinge lingers on the sea surface.View species

-

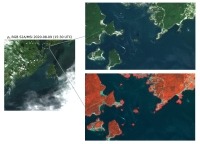

Satellite Mapping of Seaweed

Scientists use satellites to help map seaweed beds. The European Space Agency's Sentinel-2A satellite captured this image. It was taken over the Bay of Fundy on August 9, 2020. The zoomed-in images to the right highlight the coastal areas around Green's Point, New Brunswick. The top image is a true-colour image combining measurements of red, green, and blue light reflected back to the satellite. This looks like the world as we see it – the vegetation appears green. The bottom image is a false-colour image. False-colour images use non-visible wavelengths as well as visible ones. In this case, infrared (shown as red), green (blue), and red (green) are used. In the image, the vegetation appears as red, and we can see the seaweed beds much more clearly.

(Photo: Copernicus Sentinel-2A (ESA) image courtesy of the European Space Agency – ESA (August 9,2020))

-

Tide Timelapse

Video Description: From the western side of Green's Point lighthouse, we overlook the rocks of Morgan's Ledge. To our left, the sun is rising. The rocks beneath us are exposed at low tide. In sped up time-lapse footage, we watch as the tide races in and covers them. Over the six- hour tidal cycle, up to eight metres of water floods in, submerging the rocky shore and creating strong currents around the point. Clouds sweep across the sky and tendrils of steam rise from the cold sea surface. As the sun creeps to the right, the rocks gradually submerge. When the sun is directly above them, they have almost disappeared. This video has no sound.