Passamaquoddy Bay Pockmarks Accessible Exploration

Explore the Seafloor

Come for a dive in Passamaquoddy Bay! Let images and videos introduce you to some of the amazing species that live here. Once you’re back on the surface, learn about sampling methods that scientists use to collect and study seabed animals.

-

Location of Pockmarks in Passamaquoddy Bay

Pockmarks are circular depressions in the seabed. Pockmark fields are frequent in several bays and shallow coastal areas along the Bay of Fundy’s northern coast. The Passamaquoddy Bay field is the largest. It contains over 10 000 pockmarks that cover an area of 87 square kilometres. The pockmarks vary in diameter from 1 metre to 300 metres. They reach depths up to 29 metres below the seafloor. This map shows the location of pockmarks in Passamaquoddy Bay. The two lines indicate areas in which the researchers did seismic surveys to examine the geology of the seafloor.

(Photo: Reproduced with permission from Broster BE, Legere, CL (2018) Seafloor pockmarks and gas seepages, northwestern Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, Canada. Atlantic Geology 54, 1-20.)

-

Pockmark Formation 1 – Sea-Level Changes

Passamaquoddy Bay wasn’t always underwater. Around 13 000 years ago, the heavy ice sheets covering the area withdrew, allowing the earth’s crust to rise approximately 60 metres. Much of Passamaquoddy Bay was now dry land. The only water left in the area was in narrow lakes between Deer Island and Eastport, and Deer Island and Campobello. Wetlands formed, and plants grew. The coast slowly submerged until around 5000 years ago, when water covered Passamaquoddy Bay again. Mud buried the plants and wetlands. Bacteria have been slowly decomposing the buried plant material. As they digest the material, they produce gas. This is known as biogenic gas because it is produced by living organisms. The gas can’t escape easily through the thick mud covering it.

(Photo: Reproduced with permission from Shaw J, Gareau P and Courtney RC 2002. Paleogeography of Atlantic Canada 13-0 kyr. Quaternary Science Reviews 21: 1861-1878.)

-

Pockmark Formation 2 - Earthquakes

Scientists think that earthquakes might have caused the formation of some of the Passamaquoddy Bay pockmarks. Several of the pockmarks are close to the Oak Bay fault line. Hundreds of earthquakes have been recorded in New Brunswick. The largest, with a magnitude of 5.9, was on 21st March 1904. As reported in the St Croix Courier, it caused chimney tops to be “thrown to the ground with great force.” An earthquake could have caused biogenic gas pockets trapped under the seabed mud to be suddenly expelled into the water column. The escaping gas bubbles catch up sediment, which is then brought to the surface and swept away by currents, leaving holes in the seabed. Divers have seen large gas bubbles in other pockmark areas.

(Photo: St Croix Courier, Provided by Charlotte County Archives)

-

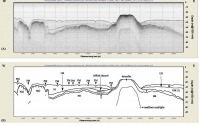

Pockmark Formation 3 - Seafloor Geology

The researchers used seismic images to examine the structure of the seafloor. Seismic images are produced by sending sound waves (seismic waves) into the seafloor. Sensors called geophones pick up the reflected wave. The different layers of the seabed bounce the waves back at different speeds. This diagram shows that the pockmarks (PM) are formed in the upper layer of seabed mud (M). The mud overlies bedrock (BR) and glacimarine sediment (GM), but several of the pockmarks are above pockets of natural gas (NG).

(Photo: Reproduced with permission from Broster BE and Legere CL (2018) Seafloor pockmarks and gas seepages, northwestern Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, Canada. Atlantic Geology 54, 1-20.)

-

DFO Pockmark Survey 1 – Pockmark Sampling

Between 2001 and 2004, researchers from Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Huntsman Marine Science Centre conducted a survey to study the Passamaquoddy Bay pockmarks. They took sediment samples to study the sediment chemistry. They videoed the pockmarks to record megafauna (like seastars) and sediment features such as holes. They took grab samples to study the creatures living in the seabed. This figure shows one of the pockmarks and the positions where the scientists took different types of samples.

(Photo: Created, with permission, from data in Wildish D, Akagi HM, McKeown DL and Pohle GW (2008) Pockmarks influence benthic communities in Passamaquoddy Bay, Bay of Fundy, Canada.)

-

DFO Pockmark Survey 2 – Seabed Video

Video Description: Fisheries and Oceans Canada took this video of the pockmarks using TOWCAM, a towed underwater vehicle that has a video camera, still camera, and floodlights mounted on it. The pockmarks themselves are too large for us to see their shape on the video, although we are actually in one. It is hard to see the seabed clearly due to the murky water. We can make out that the seabed is muddy with many small holes. These holes ranged in size from 3 to 36 cm in diameter and the scientists found them both inside and outside pockmarks. They thought these were probably formed by the escape of methane gas from the sediment. It is also possible they might be the burrows of animals like lobsters or shrimps. There aren’t many animals visible on the surface of the sediment; occasionally we see large northern sea stars. This video has no sound.

-

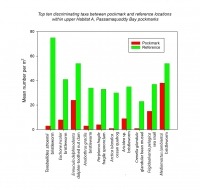

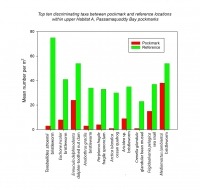

DFO Pockmark Survey 3 - Pockmark Communities

The communities living in some pockmarks are different from those of the surrounding seabed. Scientists found fewer northern sea stars inside pockmarks, clusters of orange-footed sea cucumbers on pockmark bottoms, and more abundant bacterial mats on pockmark sides. By looking at grab samples, they also found differences in the communities living in the seabed (infauna). The number and density of several infauna species were lower in pockmarks. The graph above shows the difference in abundance of the ten species that contributed the most to the difference between infauna communities in pockmarks and reference sites. Pockmarks had significantly fewer of several bristleworm species and some molluscs like the ocean quahog and the dolphin-toothed nut clam. One theory is that when pockmarks are formed, it displaces or kills benthic species. It is likely to take 5 to 15 years for communities to recover. Which would mean that in some of the pockmarks, the communities are still recovering from a disturbance that took place within the last 15 years.

(Photo: Created, with permission, from data in Wildish D, Akagi HM, McKeown DL and Pohle GW (2008) Pockmarks influence benthic communities in Passamaquoddy Bay, Bay of Fundy, Canada.)

-

Grab Sampling 1

Learn more

Video Description: Scientists use grab samples to collect the animals that live within the seabed. Studying changes in these communities can tell us how healthy the local environment is. We join the Huntsman biodiversity team on board the Fundy Spray. Using a winch, they lower a benthic grab down to the seabed. When it lands on the seabed, the loss of tension in the cable will cause its jaws to spring shut and grab a piece of the seabed. The team lifts the grab and swings it over to a frame. They release its jaws, and a large chunk of mud sloshes out into the bucket underneath. The team adds water to the mud and mixes it into a slurry (this is an excellent job for anyone who enjoyed making mud pies as a child!). They pour the slurry into a sieve. We zoom in to see the mud; a large worm crawls over its surface. They then rinse away the fine sediment using a hose. The sieve lets through particles smaller than its mesh size. The team carefully washes the sample into a tray, tips it into a net, and then into a sample jar.

-

Grab Sampling 2

Learn more

Video Description: Even after we have sieved a benthic sample, some small debris is still left. We have to sort the sample and pick out the animals. This can take several days, depending on the sample size. Huntsman technician Crystal Hiltz is sorting a benthic grab sample. Looking down the microscope, she searches through the sediment for small animals. She uses fine-tipped forceps to pull them from the sample. She separates them into four categories: worms, molluscs, crustaceans, and mixed other groups. We zoom in to look down the microscope. We see the sand moving as Crystal scans through the dish. Crystal pulls out a polychaete worm, a gastropod mollusc, and a tiny amphipod crustacean. This video has no sound.

-

Trawl Survey

Fisheries and Oceans Canada go out on regular trawl surveys to monitor Passamaquoddy Bay’s fish populations. We join them aboard the Canada Coast Guard vessel Viola M. Davidson. The deployed trawl has been towing over the seabed for 20 minutes. The crew haul in the trawl’s net, spooling it onto a large net drum. They use the deck crane to lift the fish-laden cod-end of the trawl on board. They carefully swing the crane over to the hopper they use as a sorting and counting table. They loosen the purse strings that hold the cod-end closed. The catch cascades out into the hopper, flopping and wriggling. The hopper is so full that some fish flop out over the edge. We zoom in to examine the catch. There are many winter flounder, rock crab, and even some lobster. The crew starts to sort the catch, careful in their handling of the bigger crab and lobster that can give fingers a good pinch. After they have identified and counted everything, they will return it to the sea.

-

Passamaquoddy Bay

Video Description: From the air, we look out over Passamaquoddy Bay. We start above the sandy shores of Minister’s Island, to the west side of the bay. We slowly pan around in a clockwise direction. To the north, we see Hospital and Hardwood Islands. As we turn, we see that the bay is almost enclosed by mainland shore to the north and east, and Deer Island to the south. The land surrounding the bay protects the bay from the weather. Its large open expanse means that currents are much weaker here than in the Western Isles’ narrow passages. Seabeds in the bay are mainly sand or mud. This video has no sound.

-

Squid Eggs

View species

In August and September, Atlantic longfin squid come into Passamaquoddy Bay’s sheltered waters to spawn. Females use their arms to attach gelatinous, finger-like egg capsules to seaweed or rock. They often stick their eggs onto those of other females, forming a cluster known as a sea mop. Each capsule contains around 200 eggs. The eggs in the capsule may have several fathers.

(Photo: Claire Goodwin)

-

Juvenile Ocean Pout

View species

Sheltered inshore habitats like Passamaquoddy Bay are important nursery areas for many fish species. Ocean pout spawn in hard-bottomed, sheltered areas. The female ocean pout guards her eggs until they hatch two to three months later. Juvenile ocean pouts are mainly found in shallow, coastal waters, around rocks with attached seaweed.

(Photo: Claire Goodwin)