Right Whale Identification & Tracking

Right whales have unique markings that we can use to identify individuals. Scientists have used this technique for many decades to study right whales. We can track right whale births and movements. We can also study associations, life history, age, sex, and serious injury and scarring. This technique provides information for genetic profiling, endocrinology, and health assessments.

Dive DeeperTechnology Interview

Why are right whales important?

The North Atlantic right whale is one of the rarest whale species in the world. Over 800 years of extensive hunting for their valuable baleen and oil has resulted in a significant decline in their population. The species became internationally protected in 1935, but is still hovering on the brink of extinction. Fewer than 400 individuals are left. Scientists thought they were nearly extinct until a team from New England Aquarium discovered 25 individuals in the Bay of Fundy in 1980. One reason for the slow regrowth of the population is that right whale females need to reach about nine years old to reproduce and only birth one calf every 3 to 10 years. Some right whales can live for over 60 years, but their life span is shortened by human-related mortality.

Where do North Atlantic right whales live?

We usually find right whales within 80 kilometres of the east coast of Canada and the United States. Right whales feed in northern waters (from Cape Cod to the Gulf of St. Lawrence) in the spring, summer, and autumn. In the winter, pregnant females head south to give birth in the shallow waters off Florida and Georgia. They come back north in spring to feed and suckle their calves. The Bay of Fundy is one of several very important feeding areas for right whales. In some years there have been more than 100 here in the summer and fall.

Researchers taking a tissue sample from a right whale. (Photo: Anderson Cabot Center/New England Aquarium)

Why do we need to know where right whales are going?

We need to understand where, when, and why whales are going to particular places in order to protect them. The biggest cause of death for right whales is being struck by vessels or getting entangled in fishing gear. If we understand where they’re going, we can put measures in place to reduce these incidents. Potential measures include moving shipping routes, slowing vessel traffic, and closing fishing areas. We can also modify fishing gear so it’s less likely to entangle a whale.

What else can looking at whales' movements tell us?

Looking at movements can show us other things that are affecting right whales. Starting in 2010, for the first time in 30 years, researchers saw the start of a shift.Right whales were beginning to change the areas they used in the summer and autumn. This has turned out to be a prolonged shift in habitat use. Fewer right whales were coming to the Bay of Fundy and for shorter periods of time. This coincided with fewer sightings of right whales in the Gulf of Maine starting in 2012. In 2014 we also started seeing fewer right whales south of Nova Scotia in a critical habitat area called Roseway Basin.

Has the distribution of right whales changed?

Fewer right whale sightings in their traditional habitat areas concerned scientists. In 2015 they surveyed specific areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.They looked at areas with high plankton concentrations and similar oceanographic features to the Grand Manan Basin. These surveys found many right whales were gathering in an area called the Shediac Valley in the waters between the Acadian Peninsula and the Magdalen Islands. We think that climate change may be causing right whales to move further north, into the St. Lawrence, as the availability of food changes in their traditional habitats.

How can we see where right whales are going?

Scientists use visual and acoustic (sound detection) surveys to track where right whales are. They conduct visual surveys over key areas in the right whale range using boats and planes. These surveys help us find out where right whales are feeding, socializing, and calving. Since we can identify individual whales, we can see which females have had a calf and then monitor them to see if the calf survives. Acoustic surveys use underwater recording devices to listen for whale calls. These can be fixed in one position on a buoy or on moving underwater gliders (dcs.whoi.edu). These provide near real-time location data on right whales, as well as four other baleen whale species (fin, sei, minke, and blue whales).

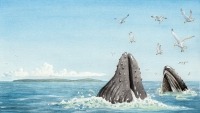

Right whales can be identified by patterns of ‘callosities’. (Photo: Nick Hawkins)

How can we identify right whale individuals?

One way to tell right whales apart is by looking at the shape and distribution of natural markings on the tops and sides of their heads. We call these raised and roughened patches of black skin callosities. Each whale has a unique pattern of callosities, like we all have unique fingerprints. The black callosity pattern also appears white or yellow from infestations of whale lice. If a whale has scars, such as from boat strikes or entanglement, we can also use these to tell whales apart. The New England Aquarium maintains a catalogue of images of whales (rwcatalog.neaq.org). When scientists spot a whale, they can search through the catalogue for the matching features to identify their individual. Whales are usually named for a distinguishing feature such as the shape of a tail marking. Names that people have given them include Bowtie, Caterpillar, Toothbrush, Bar Code, and even Wavy Gravy.

Are there other ways to identify right whales?

We can also identify right whales by looking at their genetics. We can use tissue samples to produce a genetic (DNA) sequence. All living organisms have DNA. This is what carries the instructions that tell our bodies how to grow, develop, function, and reproduce. DNA is made up of four building blocks called nucleotides: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). If we look at a particular segment of DNA, each individual will have a slightly different arrangement of these, so we can use the sequences to tell them apart. So far, scientists have sampled about 75% of the population. Scientists take tissue samples using an arrow with a specialized tip. A researcher fires the arrow from the bow of a boat using a crossbow. The arrow bounces off the whale, taking a small skin sample with it. The sequences are held in a DNA database at Saint Mary’s University.

What can whale DNA sequences help with?

We can use these genetic samples to help identify dead whales that are too decayed to recognize by their markings. We match a sequence of their skin or bone to that of a known whale in the genetic database. As well as their use for identification, the samples can tell us a lot about whale history, biology, and recovery. We can look at things such as historical population structure and the impacts of whaling and climatic changes over time. They can give information on mating patterns and reproductive success, disease resistance, and levels of inbreeding.