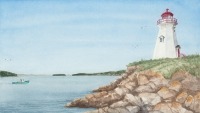

Green’s Point

Dive DeeperDense rockweed covers the rocky coastline around Green's Point. It forms thick underwater forests. These are home to creeping periwinkles, scuttling crabs, and many juvenile fishes. In the deep tidal pools on the Point's shore you might find horse mussels and sea stars. You can see many birds including common eiders and bald eagles. You might even glimpse a porpoise hunting in the tidal rapids offshore. The historic wooden lighthouse, built in 1903, overlooks the point.

Rockweed

Ascophyllum nodosum

This olive-brown seaweed grows from a holdfast that attaches onto rock. Its leathery fronds can be up to two metres long. The fronds have large air bladders set at intervals down their length. These bladders let the frond float up in the water column when the tide is in. When the tide is out, the seaweed lies over the ground. Rockweed is the dominant intertidal species in Atlantic Canada. It accounts for 50% of the primary productivity (energy produced from photosynthesis) in the Gulf of Maine. It provides food and habitat for many other species. People also harvest rockweed commercially. We use it as a fertilizer, animal food supplement, and to produce sodium alginates, which have many industrial uses.

Northern Rock Barnacle

Semibalanus balanoides

Although they look a bit like limpets, barnacles are relations of crabs and shrimps. They use modified legs, called cirri, to filter zooplankton and detritus from the water. They hold their cirri steady if there is current and beat them rhythmically if there is no current. In short, we can imagine a barnacle as a shrimp stuck by its head to a rock and kicking food into its mouth. When the tide is out they close their calcified shell plates to stop themselves from drying out. Barnacles have a penis that can be eight times their body length (the longest penis-to-body-length ratio in the animal kingdom). This allows them to mate with neighbouring individuals. After mating, the barnacle's penis degenerates and is re-grown the following spring.

Green Sea Urchin

Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis

Sea urchins are found from the intertidal to depths of over 1000 metres. They are common on rocky shores and in seaweed beds. They feed mainly on seaweeds such as kelp. If sea urchins become too abundant they can create areas with no seaweed. These are known as urchin barrens. But if there aren't enough urchins, seaweed may become over-abundant. It is important to manage pressures as far as possible to keep the ecosystem balanced. Infection by the amoeba Paramoeba invadens sometimes causes mass mortality of sea urchins. Sea urchins are also fished commercially in the Bay of Fundy—their gonads are edible and regarded as a delicacy by some people.

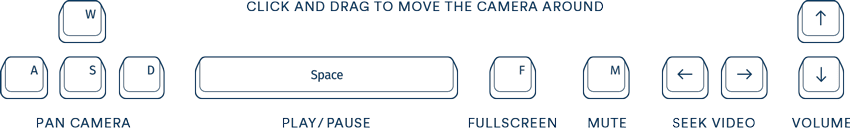

360 Video

Click and drag to move the camera around.

Video description: The divers leave the mirror-like sea surface and descend through dense fronds of rockweed. They swim over the sun-dappled seabed through the rockweed forest. One of the divers pauses to photograph and collect a specimen for identification. They spot barnacles attached to the sharp pebbles that make up the seabed. The barnacles kick their legs to feed. The divers struggle through the tangled rockweed fronds and break the surface. We see Green's Point Lighthouse behind them.

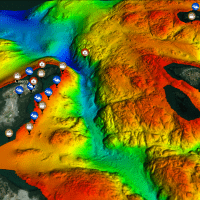

Explore the Seafloor

Come for a dive at Green's Point! Take a virtual swim along the seabed using our interactive 3D map. The seabed has been mapped using sound waves (sonar). Let images and videos introduce you to some of the amazing species that live in the rockweed forests. Once you're back on the surface, learn about the Point's historic lighthouse.

Marine Career

Seaweed Researcher

Kristen Wilson is an early career researcher at Dalhousie University and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. She studies the seaweed and eelgrass forests found around our coasts. Kristen's research focuses on mapping seaweeds and eelgrass using satellites. This helps us understand and manage seaweed habitats and how environmental changes such as climate change might affect them.

Learn moreTechnology

Satellite Remote Sensing

Remote sensing is a process that detects features on the earth's surface from a distance. Light from the sun reflects off the seafloor and is recorded by satellites. The satellites are thus able to image the world around us. This includes mapping of coastal habitats dominated by vegetation. We can distinguish areas underwater like eelgrass and rockweed beds, and kelp forests. These maps influence decisions about conservation such as marine protected areas. They also help us manage the fishery of commercially important seaweeds, including rockweed.

Learn more