Sandy Island

Dive DeeperIn this small bay on the southeast side of Sandy Island, the sun-bleached poles of a fishing weir can be seen sticking up from the water. Below the surface, the abandoned poles now provide a home for many species. Undulating in the current, forests of pink-mouthed hydroids encrust the weir pilings. Sea vases and fronds of kelp jostle for space with them. You may even catch a glimpse of a lumpsucker, frantically fanning its fins to swim clumsily between the weir poles. Giant anemones dwell in the soft sediment below, wafting their pale tentacles in search of food. Crabs scuttle and sea stars creep over the soft mud.

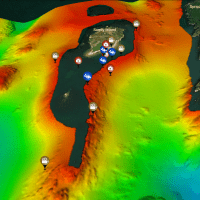

Explore the Seafloor

Come for a dive at Sandy Island Weir! Take a virtual swim along the seabed using our interactive 3D map. The seabed shape has been recreated using sound waves (sonar).

Let images and videos introduce you to some of the amazing species that live here. Once you're back on the surface, find out more about the Bay of Fundy herring fishery.

Herring

Clupea harengus

Herring is the dominant fish species in the North Atlantic. They form large shoals, feeding on zooplankton such as copepods and krill. They are an important link in the food chain between the plankton and large predators. Fish, sharks, birds, and marine mammals, including humpback whales, feed on herring. Herring are also an important commercial fishery in the area. People eat herring and their roe (eggs). Small ones are canned and sold as sardines. They are also sold for bait. Management of stocks to ensure overfishing does not occur is very important. A decline in herring can have a significant effect on the whole ecosystem.

Lumpfish

Cyclopterus lumpus

Lumpfish live offshore in winter, but migrate into shallow inshore sites, like Sandy Island Weir, in early spring to breed. They display a strong homing ability and return to the same sites year after year. Males arrive first and establish nest sites. They then court females for several hours with a ritual including nest cleaning, fin brushing, and body quivering. When persuaded, the female lays her eggs and the male fertilizes them. The male protects the eggs for six to seven weeks, until they hatch. He removes predators such as the green sea urchin. He will also fan the eggs with his fins to oxygenate them. After hatching, the larvae disperse into the sea and are often found in association with clumps of floating seaweed.

Northern Burrowing Anemone

Pachycerianthus borealis

This large white anemone can reach 45 centimetres in height with a tentacle span of 23 centimetres. It uses its many tentacles to capture prey, such as small shrimp and fish, from the seawater. The tentacles have specialized stinging cells called nematocysts that stun or kill the prey. The tentacles then transfer the prey to the anemone's mouth. The anemone has a long, thick tube that extends up to one metre into the sediment below it. It forms this tube from mucus, seabed pieces, and the sticky filaments of stinging cells. The tube is smooth and shiny on the inside. If threatened, the anemone rapidly retracts its whole body down into it.

360 Video

SCUBA divers explore Sandy Island weir

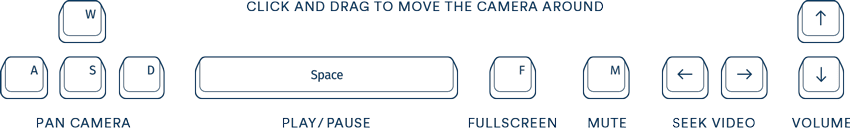

Click and drag to move the camera around.

Video description: The divers descend past trailing kelp to the bottom of the wooden pilings. We hear their inhalations and the soft tinkle of bubbles as they exhale. Once bare wood, the poles are now covered in sea vases and green sea urchins. At the bottom something catches their eye—a lumpfish. They follow it as it shakily fins along the base of the pilings. Descending onto the muddy seabed, they spot a northern burrowing anemone, its striped tentacles undulating in the current. A Jonah crab crouches at the anemone's base. Heading into deeper water, they track a longhorn sculpin as it glides over the seabed.

Marine Career

Marine Mapping Specialist

Ian Church is an assistant professor at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton. His teaching and research focus on mapping the ocean floor - the last unexplored frontier on earth.

Learn moreTechnology

Multibeam Sonar

Ian Church uses multibeam sonar to map the seafloor. From his research vessel he sends a fan of sound pulses into the water. These bounce off the seabed and back to the survey vessel. We know the speed that sound travels through water so we can calculate the seabed depth from the time it takes for us to hear the echo. Ian combines millions of sonar readings to make detailed maps.

Learn more