Moira Brown,

Marine Mammal Scientist

Moira Brown is a scientist with the Canadian Whale Institute. She studies North Atlantic right whales. She works with other researchers, industry, and government to find ways to protect this endangered species.

Dive DeeperMarine Career Interview

What do you do?

I’m a Senior Scientist with the Canadian Whale Institute on Campobello Island, New Brunswick. I’m also a Emerita Scientist with the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium in Boston, Massachusetts. My specialty is in field studies of North Atlantic right whales. I work closely with universities and government groups in Canada to protect whales. We work with marine industries, government, and other stakeholders to develop, implement and monitor protection plans. We hope these plans will protect right whales from deaths caused by human activity.

What does your typical day involve?

My typical day involves working with collaborators on various right whale concerns. The two primary issues for right whales are vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing gear. We work to reduce those threats. I focus my efforts with people in Canadian waters. As part of the Campobello Whale Rescue Team, I am part of a team that developed and runs training courses that teach others how to respond to entangled whales. I write about my research findings in reports and publications. I also develop proposals to keep the research and conservation program funded.

Do you work with many different people?

Yes, there are many teams of researchers studying North Atlantic right whales. These include scientists, conservation workers, fish harvesters, shippers, educators, and government managers. We gather once a year for the annual conference of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium. Here we update each other on science, conservation progress, and other issues (www.narwc.org). In Canada, the Canadian Whale Institute collaborates with researchers at Dalhousie University, Saint Mary’s University, and the University of New Brunswick in Saint John. We also work with several other non-governmental organizations. These include the Marine Animal Response Society, Grand Manan Whale and Seabird Research Station, Fundy East Whale Rescue, and Équipe de desmpêtrement du Golfe (an apprentice whale rescue team based in Shippagan, NB.

Moira observes a right whale at close quarters

What do you enjoy most about your job?

There are four things I enjoy most about my job. One is working with people from different industries and groups. I work with industry representatives, ship captains and fishermen, and the government in Canada. I encourage them to take great responsibility for whales, especially right whales, in their day-to-day business at sea. I also enjoy being at sea, spending time with right whales and learning more about their life history and behaviour. Another thing I like is working with collaborators on the latest in acoustic technology. I want to use this to detect right whales in the water, and see if it is helpful in creating conservation plans. Working with the Campobello Whale Rescue Team is the fourth thing I really enjoy about my job. They’re fishermen who respond to entangled whales and cut them free from lines. Working with them is very rewarding.

Moira works with the Campobello Whale Rescue Team, pictured here freeing an entangled right whale. (Photo: Anderson Cabot Centre for Ocean Life, New England Aquarium)

How did you first get into this field?

I completed my Bachelor of Education at McGill University. After this I worked as a Physical Education teacher for four years before returning to McGill to complete a Bachelor of Science. Then I started working on contract for scientists at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. They recommended field work on marine mammals to gain more experience with whales. I started as a volunteer in 1985 with the New England Aquarium (Boston, Massachusetts) at their field station in Lubec, Maine, on the Bay of Fundy.

How did you get your current job?

I noticed a scarcity in funding for right whale field studies in Canadian waters. I got together with some colleagues and we formed a not-for-profit organization. The following years were filled with proposal writing, field studies, reports, and publications. I eventually completed doctoral studies at Guelph University. I had a position for three years as a professor at the College of the Atlantic (Bar Harbor, Maine). After that I returned to full-time research at the Center for Coastal Studies (Provincetown, Massachusetts) for seven years. I then moved to the New England Aquarium for 15 years. I returned to Canada in 2016 to work full-time for the Canadian Whale Institute. I have been working for over three decades on right whales and reducing human impacts that negatively affect their recovery.

Why is this field important?

Marine mammal research is an exciting and expanding field. It’s grown tremendously in the last four decades. Researchers have described whales as ecosystem engineers, recycling nutrients and increasing primary productivity in marine ecosystems that support fisheries. We need research, especially on endangered species, to help us take the right action to protect them. For endangered and non-endangered species, new technology can help us learn more about these elusive animals and what threatens them, and improve their survival.

Any advice for people wanting to work with whales?

There are many ways to get involved in marine mammal research. There are field studies, life history biology, laboratory work on biochemical analyses, acoustics, veterinary pathology, biological and physical oceanography, animal behaviour, population modeling, and techniques such as satellite monitoring and the use of drones. All these areas need a background in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics. You can also work in this field with training in education, marine policy, resource management, or even as a museum curator or archivist.

What inspired you to work in marine biology?

Curiosity about the marine environment inspired me. I’s a great privilege to be able to work on something you’re curious about—the learning never ends. So many people write about the bounty that used to be in the oceans. I’m inspired by the need to take more responsibility for the oceans and their inhabitants. We need to do this so there is something left for future generations.

Why is the Grand Manan Basin important to Right Whales?

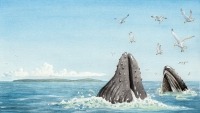

We know the Grand Manan Basin was an important seasonal feeding area for right whales. They gathered here in the summer and autumn to feed on plankton; a copepod called Calanus finmarchicus is the staple of their diet. The currents in the Bay of Fundy concentrate the copepods into dense patches. But in the last 10 years, as the waters warm, fewer right whales have been coming to the Grand Manan Basin. Plankton concentrations are now much lower, perhaps too low to provide enough food for right whales.

Where are the right whales moving to?

Not all, but at least half of the individuals have shifted their late spring, summer, and autumn habitat north to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. We know this because we can recognize individual right whales by their distinctive markings (rwcatalog.neaq.org). We take photographs and keep records of where we’ve seen particular whales. Only time will tell if the plankton and the right whales will return to the Grand Manan Basin in the numbers seen before. You can find out more about right whale movements on WhaleMap.

What are some of the issues for Right Whales? How can we help protect Right Whales?

The two most critical issues for North Atlantic right whales are vessel strikes and entanglement in fixed fishing gear. These can cause serious injury or even death. Eighty-six percent of catalogued right whales have been entangled once, and another 50% twice. Adult females that have been entangled take longer to reproduce than other mothers. We need to reduce the impact of human activities on right whales. To do this, scientists have worked with fishermen, vessel operators, and governments for decades to design and establish protection plans. Such plans include moving shipping lanes away from large gatherings of whales, or having vessels reduce their speed in areas where whales are plentiful. These would reduce the chances of whales being struck by vessels. Governments may also implement gear modifications or close fishing areas to prevent gear entanglement.

Are the protective measures working?

We’ve made some progress on vessel strikes, but entanglements continue to present a serious threat to right whale survival. Over the last decade, right whale populations have shifted to areas where there are no protective measures in place. Climate change is the likely driver of this shift. In 2017, right whales experienced an unusual mortality event involving 12 deaths in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and another five in US waters. For those animals where we could tell the cause of death, it was vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing gear. Government has implemented many conservation measures to protect right whales, and mariners have complied. These are always being adapted as we learn more. We still have a great deal of work to do, but hopefully we can reduce and ultimately end negative human impacts on right whales and other marine animals.

Entanglement can be a serious problem for right whales. (Photo: Anderson Cabot Centre for Ocean Life, New England Aquarium)