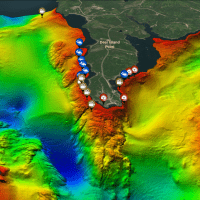

Deer Island Point

Dive DeeperAt Deer Island Point, the rushing waters of the Western Passage and Head Harbour Passage collide. This creates the “Old Sow,” the western hemisphere's largest whirlpool. Abundant life crowds the rocky seabed here, feasting on the plentiful plankton supplied by the strong tides. This in turn attracts fish and crabs to feed on the filter feeders. If you look carefully, you can spot the snaggle-toothed faces of wolffish peering out of their rocky dens.

Explore the Seafloor

Come for a dive at Deer Island Point—if you dare brave the whirlpool! Take a virtual swim along the seabed using our interactive 3D map. Let images and videos introduce you to some of the amazing species that live here. Once you're back on the surface, find out about the animals that live in this tide-swept environment and how scientists collect and identify them.

Atlantic Wolffish

Anarhichas lupus

This large fish can grow up to 1.5 metres long and reach 18 kilograms in weight. They can live for over 20 years. They are found on rocky seabeds down to depths of around 500 metres. The wolffish uses its powerful teeth to crush its prey. It eats invertebrates such as sea stars, urchins, molluscs, and crabs. Scientists think that they control the density of species such as sea urchins. Adult wolffish move inshore to mate. The female lays her eggs in a rocky den in bedrock or under boulders. The male stays in this den to guard them until they hatch; he does not eat during this period. Wolffish live in cold water and can experience sub-zero temperatures during the winter. Because of this, their bodies produce antifreeze proteins. These proteins help inhibit the growth of ice crystals in their blood.

Horse Mussel

Modiolus modiolus

Horse mussels attach themselves to the seabed using tough fibres known as byssal threads. They attach to rocks and shells and later become partly buried in sand or mud. They are a long-lived species: most adults are over 25 years old and can live for more than 50 years. Individuals often clump together and may form extensive beds or reefs. Scientists have recorded bed densities of up to 158 mussels per square metre in the Bay of Fundy, and 400 mussels per square metre elsewhere. Horse mussel beds provide shelter, nurseries for young, and feeding grounds for many species. This includes commercially important species such as scallops.

Canadian hymedesmia sponge

Hymedesmia canadensis

This red sponge forms small patches on bedrock. Individuals can be up to 10 centimetres in diameter and a few millimetres thick. It has prominent circular pore sieves over its surface. Pore sieves are collections of ostia, or small pores that water is drawn in through. Sponges are simple animals that feed on small particles in the seawater. 80% of their diet is bacteria-sized particles (less than 0.5 micrometres in diameter). They suck seawater into a network of canals in their body using a current generated by cells called choanocytes. The choanocytes also capture the food particles. Sponges have a skeleton made of silica spicules and scientists use the shape of these to identify them. Brian Ginn, a former student at University of New Brunswick, discovered this new-to-science species while doing his Masters research project in 1998. It was first found in Little Letete Passage, close to Deer Island.

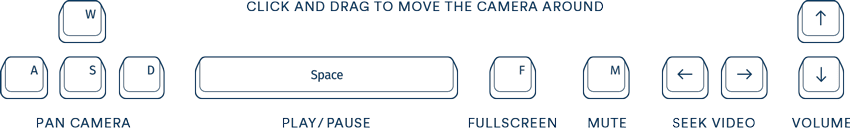

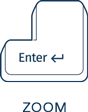

360 Video

SCUBA divers study wolffish at Deer Island Point

Click and drag to move the camera around.

Video description: Through the green waters, the divers spot a wolffish peeking out of its den between boulders. We hear the divers’ inhalations and the soft tinkle of bubbles as they exhale. Further along in another den, they spot a second wolffish. A dense turf of northern lamp shells, sponges, sea vases, and northern red anemones covers every inch of the bedrock above the den. The divers watch as the wolffish ventures from the den and seizes a horse mussel in its powerful jaws. It crunches and crushes the mussel shell with its teeth. The divers are surprised as a second wolffish emerges from the back of the den to join it in feeding.

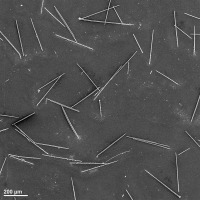

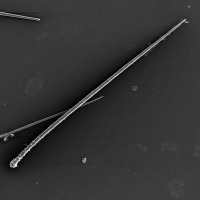

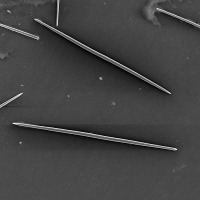

Interactive Microscope

To identify sponges we have to look down the microscope. Many sponges have skeletons made out of silica (glass). We call the individual elements within the skeleton spicules. The shapes and sizes of the spicules help us determine the species. We dissolve the spicules out of the sponge tissue using acid or household bleach, and then we can mount them on microscope slides. This specimen is the Canadian Hymedesmia sponge, Hymedesmia canadensis. It has spiny acanthostyles, smooth styles, and tiny, semi-circular chelae. Can you spot them on this microscope slide? We took these images using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), but you can also look at sponge spicules using a standard compound microscope.

Marine Career

Museum Curator

Claire Goodwin is a research scientist and curator at the Atlantic Reference Centre (ARC). Her job involves looking after the thousands of specimens in the ARC’s museum collections. She studies sponges and goes SCUBA diving to find sponge species new to science.

Learn moreTechnology

Museum Collections

The Atlantic Reference Centre is a research museum of Atlantic Canadian marine life. It is known as the ARC, like Noah's ark, because the curators like to keep an example of everything they find. The museum is a partnership between Huntsman Marine Science Centre and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. It has over 150 000 lots of specimens of marine animals ranging from tiny plankton to huge sharks. Most of the specimens come from the waters of Atlantic Canada. Scientists use the ARC collections for their research and to help them identify animals.

Learn more