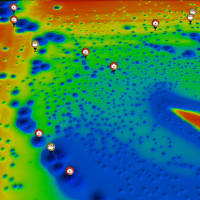

Passamaquoddy Bay Pockmarks

Dive DeeperOn the northwest side of the Passamaquoddy Bay, over 11 000 strange conical depressions cover the seabed. These “pockmarks” can be over 300 metres in diameter (that’s longer than five hockey rinks) and 50 metres deep. Scientists think that methane gas forms the pockmarks as it escapes from the seabed. Bacteria made the gas as they digested buried vegetation. Only an occasional sea star or sea cucumber is visible on the surface here. But dig down into the sediment and you will find a sub-surface city of worm tunnels, bivalve burrows, and tiny crustaceans. Discover how and why scientists study these hidden communities.

Northern Sea Star

Asterias rubens

This sea star is a predator, feeding on urchins, worms, and other sea stars, as well as bivalve molluscs like mussels and scallops. Under their legs they have small tube feet that they operate using their water vascular system—a hydraulic network of tubes and valves. Each tube foot has a valve that, when closed, creates pressure that extends it. Clams and scallops are too big to fit in their mouths—but that doesn't stop these sea stars. They use their tube feet to suction onto bivalve prey and pull their shells apart. They then eject their stomach from their mouth and into the bivalve's shell. After digesting the soft tissues of the bivalve they slurp it down.

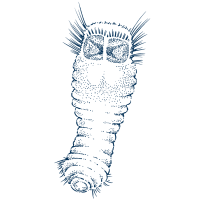

Mud Owl

Sternaspis fossor

This plump worm lives in mud and sand seabeds. They burrow head down, leaving the gills on their posterior exposed. They have a pair of large, round, ventral shields that look a bit like owl eyes and a body shaped like a resting owl. This gives them their common name “mud owl.” They feed by turning their pharynx (the top part of their digestive tract) inside out. They then use it to scoop fine particles from the seabed and feed on the organic material in these. William Stimpson described this species in 1854 from specimens found near Grand Manan in the Bay of Fundy.

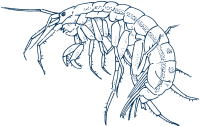

Amphipod

Casco bigelowi

This distinctive red-and-white-striped amphipod lives in burrows in muddy seabeds. Females keep eggs in a brood pouch as they develop. After hatching from the brood pouch, juveniles remain in the female's burrow for two to three months until they become more than half the size of an adult. Females feed, clean, and defend the juveniles from predators. As the juveniles increase in size, females will expand their burrow systems to accommodate their growing family. Charles Blake described this species from just over the border in Casco Bay, Maine. He named it for Dr. Robert P. Bigelow, a biologist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Explore the Seafloor

Come for a dive in Passamaquoddy Bay! Take a virtual swim along the seabed using our interactive 3D map. The seabed has been mapped using sound waves (sonar). Let images and videos introduce you to some of the amazing species that live here. Once you're back on the surface, learn about sampling methods that scientists use to collect and study seabed animals.

Interactive Microscope

It is only occasionally that we find large animals on the surface of soft seabeds. But dig down into the sediment and we find thousands of animals. We call these creatures that live in the seabed infaunal benthos. Many of the species living here are so small that we need to use a microscope to identify them.

Marine Career

Taxonomic Technician

Crystal Hiltz is a taxonomic technician in the Huntsman's Taxonomy and Biodiversity research laboratory. She uses physical characteristics to identify marine animals and plants. This work adds to our understanding of the diversity of life in our oceans, and the impact of both natural and human actions.

Learn moreTechnology

Grab Sampling

Not all seabed life is immediately apparent. As well as the familiar sea stars and crabs that dwell on the seabed surface, there are hundreds of thousands of tiny animals that live inside soft seabeds. We sample these by using sediment grabs to remove a chunk of the seabed, along with the animals that live in it. We then look at the grab sample under the microscope and identify the animals present. This can tell us a surprising amount about our marine environment.

Learn more